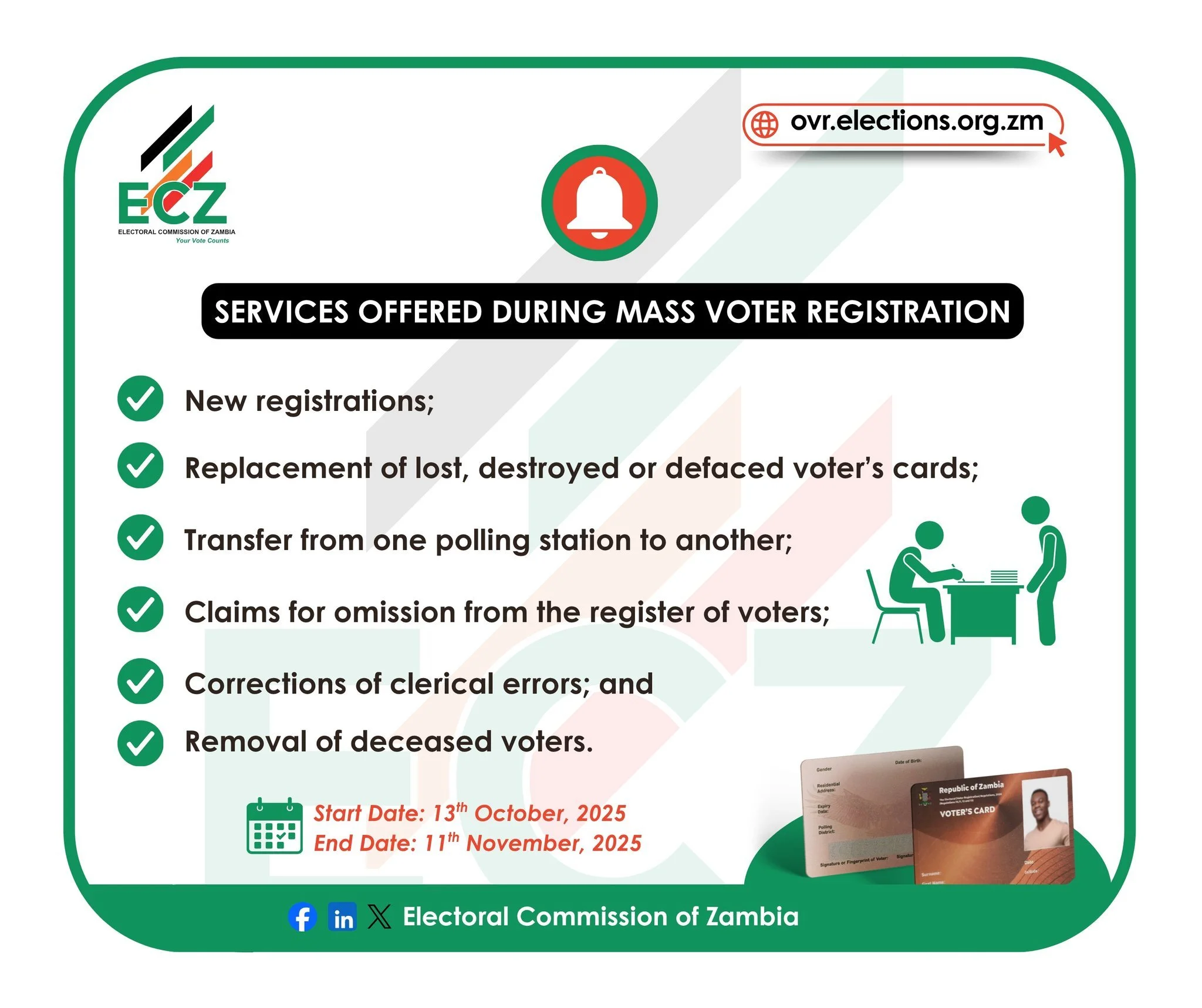

ECZ infographic displaying key Mass Voter Registration details

The Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ), pursuant to the Constitution of Zambia (Amendment) Act No. 2 of 2016, Article 46, is facilitating the registration of eligible citizens as voters. Following the 2021 General Elections, on 1st June 2022, the ECZ commenced conducting Continuous Voter Registration across 30 districts countrywide.

Building on that, the Commission is now conducting a Mass Voter Registration (MVR) exercise from 13th October to 11th November 2025 across all 156 constituencies, targeting approximately 3.5 million eligible voters. This will add to the 7.07 million already registered as of 25th February 2025. The MVR is being carried out alongside the Online Pre-Voter Registration (OVR) for first-time voters, which runs from 15th September to 3rd November 2025.

On the commencement day of the MVR on 13th October 2025, I went to Mahatma Gandhi Secondary School, one of the voter registration centres in Munali Constituency, to unofficially observe and interact with the Assistant Registration Officer. I returned the next day to both further observe and register as a voter myself. My registration involved updating my new address and polling station details from those I used during the 2020 registration. This is one of the six (6) voter registration services ECZ is offering during this exercise; they are also doing new registrations, replacement of lost, destroyed, or defaced voter’s cards, claims for omission from the register of voters, corrections of clerical errors, and removal of deceased voters.

ECZ infographic about voter registration services

From my two-day observation and registration experience, I was impressed with the ECZ’s coordination with the Zambia Police in assisting people who have lost their voter’s cards. They can obtain a police report right at the registration centre, eliminating the hassle of having to go to a nearby police station and return. This simple coordination effectively removes a major barrier to participation.

Another plus for the Commission is the provision of an alternative power supply at Mahatma Gandhi. This is especially commendable considering that ZESCO recently reduced the power supply to only four hours per day due to “extreme challenges in electricity generation and access.” Since registration runs from 08:00 to 17:00, the availability of a standby generator ensures uninterrupted service.

The registration process itself is relatively swift, combining manual and digital steps. It took roughly less than 10 minutes per registration. However, if the number of registrants increases significantly, that duration may still be too long. I believe there is room to streamline and reduce registration time even further.

ECZ infographic about OVR and MVR

As a communications professional, I am particularly impressed by the Commission’s communication efforts, both online and offline. The ECZ Facebook page, for instance, is abuzz with infographics, live coverage, and voter registration promotional content. Beyond social media, they are also active on radio and television.

Closer to home in Mtendere, I’ve heard loudspeaker announcements broadcast in local languages inviting eligible citizens to register. Such localized outreach is fundamental to ensuring increased participation. From these efforts, I foresee many citizens, especially youth, women, and persons with disabilities, turning up to register, not only at Mahatma Gandhi but across the country.

That said, while there are clear wins, there is still room for improvement in three key areas:

1. Further Digitising the Registration Process

Though ECZ already appears to be digitising the registration process, as shown by the Online Pre-Voter Registration system, which allows first-time voters to submit their details online before visiting a physical centre for verification and card printing, I still foresee a kerfuffle for both officers and registrants at the physical centres. During my registration, the officer manually entered the data letter by letter, making the process long. Imagine if ECZ upgraded its system to allow NRC scanning, automatically capturing details such as name, date of birth, and NRC number. Digitising the registration process would make data entry faster, more accurate, and more efficient, leaving the registration officer with only a few clicks to complete the process.

2. State and Location of the Registration Centre

At Mahatma Gandhi, it is impressive that the voter registration is taking place in a classroom accessible with a ramp; however, this is happening during lessons with about 50 pupils in it. Only a third of the room is reserved for the registration officer and a police officer who is administering on-site police reports for lost voters’ cards. When I was registering, there were about five of us, but imagine 20 people arriving at once. It would be chaotic.

The space is simply not adequate for large numbers, and pupils also need a quiet learning environment. Besides, this is happening in the October heat without air conditioning. Instead, they can set up the registration in a separate, unoccupied room with better ventilation and more space.

3. Strengthening Stakeholder Engagement

I encourage all stakeholders, including civil society, media, and citizens, to actively publicise this democratic process, which directly affects the quality and integrity of our elections in 2026. Actively mobilise youth, women, and persons with disabilities to register, and observe how the registration is conducted.

Above all, let us each take responsibility by going to register as voters. Check for a voter registration centre near you in phase one of the Mass Voter Registration exercise, HERE.

Gerald sikazwe

The author works as CYLA’s Communications Assistant.